Infecting mosquitoes with bacteria so they can't infect us with viruses like Zika and dengue

Mosquitoes and their itchy bites are more than just an annoyance. They transmit dangerous viruses with deadly consequences – making them themost lethal animal on Earth。这是一个Aedes aegyptiandAedes albopictusmosquito species that are behind outbreaks ofdengue virus,Zika virus,yellow fever virusandChikungunya virus, responsible for over100 million human casesaround the world annually. And they'reexpanding their habitataround the world as theglobal climate warms, bringing them into contact with more potential victims who haveless immunity and increased susceptibilityto these mosquito-transmitted viruses.

A vaccine can provide the recipient with immunity to one or two of these viruses at a time. But there's another way to tackle these diseases: by going after the insects. Targeting the mosquito population as a whole or their ability to transmit disease takes aim at all these viruses at the same time.

As the U.S. enters another mosquito season, mosquito control districts inFloridaandCaliforniaare preparingnew strategies to combat mosquitoesand the viruses they transmit. They're trying out one of two new mosquito management methods made possible by a bacterium calledWolbachia pipientis。

A bacterium that's our enemy's enemy

Wolbachiaare bacteria naturally found in insects throughout the world. They live inside a host organism's cells. From there,Wolbachiaare able to manipulate their host in many ways – things likeincreasing the number of eggsa host lays or evenchanging the host's sexfrom male to female by manipulating its hormones.

Researchers discovered in 2008 thatWolbachiain fruit fliesprotect their hosts from fruit fly viruses。That realization got them wondering: CouldWolbachiaalso protectAedes aegyptimosquitoes from viruses that cause human diseases?

Aedes aegyptimosquitoes don't naturally carryWolbachia。But consistent with the fruit fly studies, when researchers infectedAedes aegyptiin the lab, the viruses they carryreplicated less。Fewer of the infectious bits of the disease-carryingvirusinside the mosquito meant disease transmission was limited – they were less likely to be passed on when mosquitoes fed on their prey.

Researchers inAustralia,United Statesand elsewhere are currently investigating the reasons whyWolbachialimit viruses. Some hypothesizeWolbachiaimproves themosquitoes' immunity to the virus, while other research, including my own, suggestsWolbachiasteals key nutrientsthe virus needs. Both may be true.

The real need to employ this strategy now is motivating field trials to releaseWolbachia-infected mosquitoes in several regions of the world.

Vector competency: The female approach

Only female mosquitoes bite and transmit viruses. Thus, the most powerful approach to reducing virus spread is limiting viruses in the female mosquito.

Wolbachiabacteria are transmitted from mother to offspring. If you introduceWolbachia-infected female mosquitoes to a population, all offspring will haveWolbachia– and therefore be less likely to transmit disease-causing viruses.

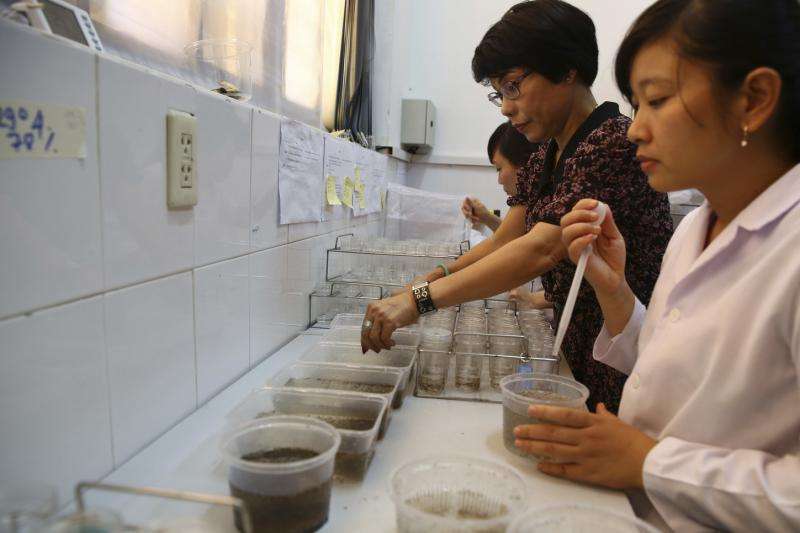

This strategy is used by theEliminate Dengueprogram, a nonprofit collaboration employing seven research institutes around the world. In test areas, Eliminate Dengue has successfully incorporatedWolbachiainto mosquito populations.

In this context, an interesting aspect ofAedes aegyptibehavior is their tendency not to travel far. In fact, a highway is a sufficient barrier toprevent mosquito spread。When researchers set up a release site in one city or town, they don't see their mosquitoes travel to other areas.

This allows for controlled studies, as well as the release of these mosquitoes only where it's been approved. The limited spread and isolated sites used were important factors in thedecision to allow mosquito releases in the United States。

Eliminate Dengue is not yet active in the U.S. Instead, the U.S. is taking a different approach, looking to male rather thanfemale mosquitoes。

Population control: The male approach

MosquitoMateis a company developed out of the University of Kentucky in Lexington by medical entomologist Stephen Dobson. Partnering with theFlorida Keys Mosquito Control District,y started therelease of 40,000Wolbachia-infectedmale mosquitoes per week this spring。

The strategy relies on a phenomenon calledcytoplasmic incompatibility (CI)to reduce mosquito populations. CI occurs when a male mosquito infected withWolbachiamates with an uninfected female. BecauseWolbachiais transmitted through the female egg, the offspring will beWolbachia-free. ButWolbachiahas already altered the father's sperm DNA in a way that allows offspring to survive only if the fertilized egg hasWolbachia。Since the infected males will come in contact only with the naturally occurringWolbachia-free population, their offspring will die during embryonic development – the eggs won't hatch.

And unfortunately for the mosquitoes, females store sperm inside them to continuously fertilize their eggs. This means that the female mosquito's first mate will be the father of all her offspring. So even if a female just mates again, once she's partnered with aWolbachia-infected male, all her offspring will not be viable.

The Florida Keys Mosquito District is not limiting its attack tojust one approach。BeyondWolbachiaand more traditional strategies, they're also partnering withOxitec, a genetic engineering company. Like MosquitoMate, Oxitec also releases male mosquitoes. But, in place ofWolbachia, Oxitec genetically modifies its mosquito tocontain a self-limiting gene that causes offspring to die。

The goal remains the same: Release males into the environment that will mate with females and cause all offspring to die, eventually leading to a mosquito population crash.

Male and female strategies share one goal

每一个Wolbachia蚊子策略有其优点:女性的美联社proach is broad-reaching and should directly decrease disease transmission. The male strategy effectively lowers the local mosquito population, without releasing female nuisance mosquitoes.

The male release strategies are an important "right-now" fix, but they'll require an annual, costly release becausemale mosquitoes– with either MosquitoMate'sWolbachiaor Oxitec's self-limiting gene – cannot pass on to the next generation their crucial trait. When these males are not being released, fertile wild males will mate with females and the population will rebound.

Eliminate Dengue's female release strategy is sustainable long-term, but it takes extensive monitoring to ensure the initial establishment of mosquitoes. While MosquitoMate and Oxitec do not disclose their costs, Eliminate Dengue hopes to make their system affordable at a cost ofapproximately US$1 per person。

Some members of the public haveadvocated against these kinds of mosquito release programs, particularly when the mosquitoes have been genetically modified, as with Oxitec's transgenic insects. While the United States Department of Agriculture received2,600 responses to the Oxitec plan, only one responsewas filed regarding MosquitoMate's non-GMO strategy.

In the U.S., mosquito control districts are taking a cautious approach. They're first trying the two nonpermanent male strategies in small areas. The Florida Keys will beevaluating mosquitoes on their Stock Island release site for 12 weeks。We should know how effective maleWolbachia-infectedmosquitoesare at reducing populations by late summer.

This article was originally published onThe Conversation。Read theoriginal article。![]()