Scientists create nanobody that can punch through tough brain cells and potentially treat Parkinson's disease

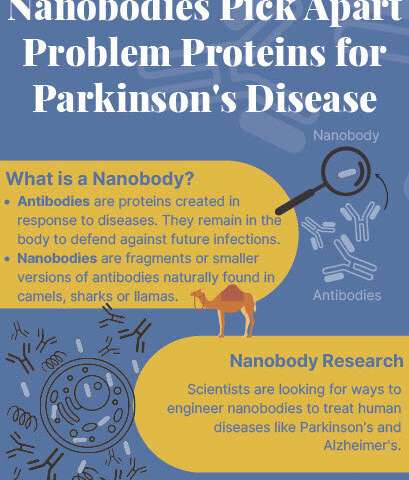

Proteins called antibodies help the immune system find and attack foreign pathogens. Mini versions of antibodies, called nanobodies—natural compounds in the blood of animals such as llamas and sharks—are being studied to treat autoimmune diseases and cancer. Now, Johns Hopkins Medicine researchers have helped develop a nanobody capable of getting through the tough exterior of brain cells and untangling misshapen proteins that lead to Parkinson's disease, Lewy body dementia, and other neurocognitive disorders caused by the damaging protein.

The research, published July 19 inNature Communications, was a collaboration between Johns Hopkins Medicine researchers, led by Xiaobo Mao, Ph.D., and scientists at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. Their aim was to find a new type of treatment that could specifically target the misshapen proteins, called alpha-synuclein, which tend to clump together and gum up the inner workings ofbraincells. Emerging evidence has shown that the alpha-synuclein clumps can spread from the gut or nose to the brain, driving the disease progression.

In theory, antibodies have potential for zeroing in on clumping alpha-synuclein proteins but the pathogen-fighting compounds have a hard time getting through the outer covering of brain cells. To squeeze through tough brain cell coatings, the researchers decided to use nanobodies, the smaller version of antibodies.

Traditionally, nanobodies generated outside of the cell may not perform the same function inside the cell. So, the researchers had to shore up the nanobodies to help them keep stable within a brain cell. To do this, they genetically engineered the nanobodies to rid them ofchemical bondsthat typically degrade inside a cell. Tests showed that without the bonds the nanobody remained stable and was still able to bind to misshapen alpha-synuclein.

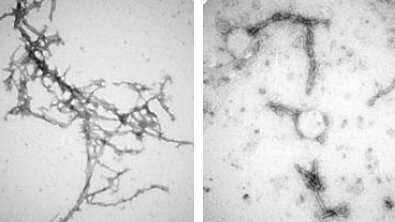

The team made seven, similar types of nanobodies, known as PFFNBs, that could bind to alpha-synuclein clumps. Of the nanobodies they created, one—PFFNB2—did the best job of glomming onto alpha-synuclein clumps and not single molecules, or monomer of alpha-synuclein. Monomer versions of alpha-synuclein are not harmful and may have important functions in brain cells. The researchers also needed to determine if the PFFNB2 nanobody could remain stable and work insidebrain cells. The team found that in live mouse-braincellsand tissue, PFFNB2 was stable and showed a strong affinity to alpha-synuclein clumps rather than single alpha-synuclein monomers.

Additional tests in mice showed that the PFFNB2 nanobody cannot prevent alpha-synuclein from collecting into clumps, but it can disrupt and destabilize the structure of existing clumps.

"Strikingly, we induced PFFNB2 expression in the cortex, and it prevented alpha-synuclein clumps from spreading to the mouse brain's cortex, the region responsible for cognition, movement, personality and other high-order processes," says Ramhari Kumbhar, Ph.D., the co-first author, postdoctoral fellow at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

"The success of PFFNB2 in binding harmfulalpha-synucleinclumps in increasingly complex environments indicates that the nanobody could be key to helping scientists study these diseases and eventually develop new treatments" says Mao, associate professor of neurology.